I recently read Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki, at the recommendation of a friend. I am generally suspicious of people dolling out multimillion-dollar advice in a “tell-all” book but it does have 32 million copies sold, 4.1 rating on Goodreads, and comes with a bright sticker proclaiming it is “celebrating 20 years as the #1 personal finance books of all time!” (which frankly sounds like something Borat would say).

As expected the book is full of highly dubious accounts of events and questionable financial advice. However, it IS the number one personal finance book of all time. So if I talk one person down the financial ledge, that this book is, then the effort is worth it and it is only fair I am named the number #1 personal finance advisor of all time!

Who is really boss?

Kyosaki is clearly big on the idea of working for yourself. He has few flattering things to say about people working 9-to-5 corporate jobs and sees that “rat race” life as the way to financial ruin. In his mind, a boss is someone who does as she pleases and has no one to respond to, while employees are feeble creatures on their knees begging for their jobs (imagery he actually uses in the book).

While it is appealing to think in terms of boss and subordinate, CEOs have long understood the importance of keeping employees happy. Take for example Google. One of the most profitable companies in the world and most respected brand names. Allegedly Google’s job acceptance rate is 0.2%. For comparison, Harvard’s is c. 5%. It is 25 times easier to get into Harvard than into Google. Google had a lucrative a long-running contract with the Pentagon, which the IT giant chose to terminate last year. Why the change of heart? Google employees were upset that they were selling services to the military. But weren’t employees voiceless masses who are forever afraid to raise a hand? Turns out even when you are one of the most sought-after employers on the plant you can’t afford to neglect your employee’s desires.

On the flip side, I had a friend who ran her own business. She was providing shipping from the Ikea store in Brooklyn to residents in New York. Most young New Yorkers don’t own a car, and Ikea’s shipping offering was expensive and inconvenient. On paper, she owned the business and could do as she pleases. She leased a van and hired drivers. However, it was a low value add business. After paying the van lease and salaries she barely had anything left. She could not cut down costs, as drivers have other opportunities to ferry all kinds of goods, and the lease company would take back the van if she fell behind on payments. These companies are called “zombie companies” – not quite dead but never making enough money to pay the owner. She ended up closing the business.

In economic terms, negotiating power has nothing to do with your title but the relative elasticity of supply and demand for labor. In more layman terms, when there is high demand for software engineers and there is a limited supply of them, they can push even Google around. It is also curious to note that Cristiano Ronaldo and LeBron James are both billionaires. They are also both salaried employees working for a club owner. If my options are an Ikea delivery business owner or a billionaire athlete employee, I would stay in the “rat race”, thank you very much.

Big houses are liabilities but buy them to get rich… or was it the other way around?

Kyosaki has a funny way of talking about financial statements. It involves a lot of pictures with arrows going every which way, with grave warnings here and there for good measure. One of the points he makes early is that expensive houses are actually liabilities, as they constantly suck in your money, but then much of his investing advice is based on continuously buying more expensive houses.

Going away from the urban legends and questionable maths in the book, here are instead three pieces of advice on housing that I believe should hold true in most situations:

- Buying is on average better or the same as renting

- Buying your primary residence with debt can be advantageous, if you live in a large diversified local economy (i.e. New York, Chicago, London, Paris)

- Real estate portfolios are not suitable investments for most people

Buying is on average better or same as renting

Renting or buying has to be theoretically the same. If rents are cheap more people will rent, if buying is cheaper more people will buy, in the long run, it stands to reason they have to be roughly equal, if people can freely choose one of the other. However, people cannot always freely choose. If it is cheaper to rent potential buyers can move into the rental market. If it is cheaper to buy, not all renters can become buyers. The average American family has $8,863 in savings, while the average house costs $368,000. In addition, there are credit score requirements (or at least there are now after the housing crisis). Therefore, if you are lucky enough to be able to afford a house, you might be playing in a less crowded market. Of course, you might also be unlucky enough to buy in a bubble. House prices sometimes rise dramatically and unsustainably as a bunch of private equity and individual investors start flipping houses (possibly inspired by our friend Robert K) but those happy days don’t last very long, as we saw in 2008.

Buying your primary residence with debt can be advantageous, if you live in a large diversified local economy

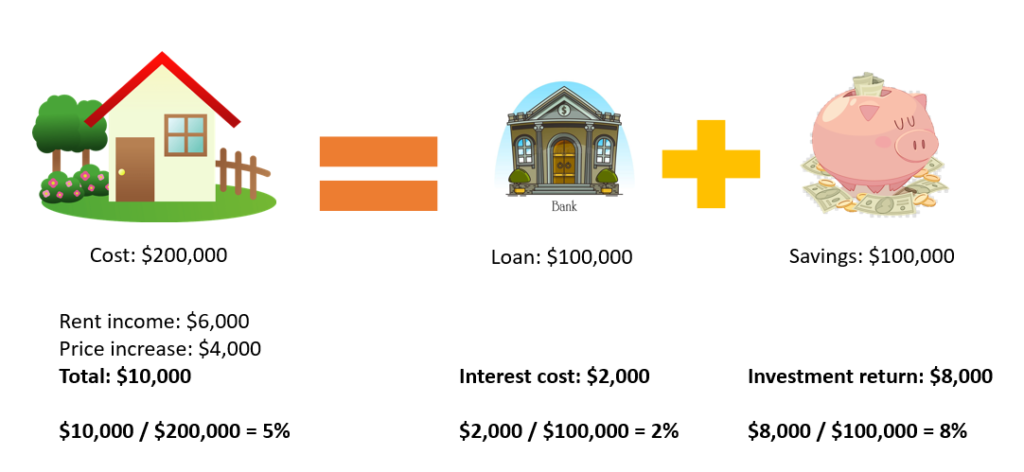

Buying a house is a unique investment opportunity that we don’t get outside of real estate, mainly because of debt. If you go to the bank and ask them for $100,000 to start a promising app, they will laugh at you. If you say you are buying a house, they will gladly finance you, and at rock bottom interest rates, at that. Cheap debt has a peculiar property (oftentimes referred to as leverage or financial engineering), which amplifies positive (and sadly negative) returns. You can find a detailed example at the bottom of the page, but the basic intuition is the following: Because debt is very cheap these days, it can increase the return on the equity you put in the home. If you buy a house with savings for $200,000 and make $10,000 in one year in either rent or price appreciation you returned 5% on your investment. If you financed half of the purchase ($100,000) with cheap debt, say at 2%, you will pay $2,000 in interest. Then your earnings are $10,000 – $2,000 = $8,000. However, since you only needed to put up $100,000 of your own money, the rest was debt, you managed to return 8% on your investment, more than the 5% if you had financed with savings only. Note, if you lost money, the loss would also be magnified so this is not a magical money machine, although some aggressive investors often forget that. Since on average house prices go up in the long run, and rents are positive, you can expect to make an increased return. Then after retirement, you can sell off the house and live comfortably off of the proceeds. However, you need to think carefully about what market you are buying into. Some communities are entirely dependent on one big employer, for example, General Motors. When a plant closed, there were no jobs left, no one wanted to live there and houses became worthless. If you are going to buy, buy in a diversified large market, like New York, Chicago, Paris, Sydney, which are unlikely to be deserted in 20 years, should one business fail. If you happen to live in a small community, rent in your community and buy in a big market.

Real estate portfolios are not a suitable investment for most people

The trick above, even with my words of warning, might seem like easy money. You can replicate it 100 times and have that nice passive income Kiyosaki talks about. Turns out owning real estate outside of your primary residence is difficult. If you don’t live at the property, you have to manage it. You will likely pay your mortgage but tenants might not always pay rent fully or promptly. You won’t trash your own place but tenants might. Dealing with tenants can be difficult, time-consuming, and costly. You are also very invested in maintaining your own home with frequent repairs and general upkeep. Tenants are often less careful, and having to run around town fixing tenants’ apartments is not as much fun. Also, managing tenants’ whims and constantly looking for deals hardly qualifies as “passive income” – it sounds pretty hands-on to me. In addition, real estate investments are illiquid. If you need the cash for a medical emergency for example, or another great investment, you cannot exit in a day, or sometimes even a month. You also need to pay brokers, appraisers, deal with documentation, title searches, etc. Further, real estate is a very chunky investment. You can’t put away $200 at the end of a month and buy a tiny little house. You have to save up for a down-payment, which could take years. Finally, real estate is ultimately one market – houses. It is not diversified, and in a recession, all your investments will likely go down in value simultaneously, which is what happened in 2008.

For most investors, all these issues can be addressed by owning a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. It requires no upkeep, you can invest small sums incrementally, it can be incredibly diversified and countercyclical, and it can be cashed in at any time.

There is no free lunch

Towards the end of the book, Kiyosaki recounts a string of fantastic deals. Starting with $5,000 and making millions of dollars in just a couple of years. Those may or may not be real, but it is true that in hindsight we can find amazing investment opportunities. Monster, the energy drink, has apparently returned 70,000% over the last 20 years. In 2020 alone a Chinese company called “Future FinTech Group” (coincidentally, also something I feel Borat would come up with) is up 404%. These assets are at the time of investment incredibly risky, even if they turn out great later. The problem is, we don’t know which ones will turn out great. In general, if you take a lot of risks, some investments will be very successful and some will be a disaster. You will hear seasoned investors say “even a broken clock is right twice a day”. The question is once you account for all the wins and losses are you ahead? Venture Capital firms specialize in picking winners. They dedicate an incredible amount of resources and hire some of the smartest people around and even they broadly perform, as well as the public stock market (There are different ways of measuring but for more detail lookup Steve Kaplan’s paper)

Do I believe Robert Kiyosaki is a better investor than the best and brightest in Silicon Valley – maybe. Do I think I can repeat his alleged success following what he has written in the book – no way. Higher returns only come with higher risk. If you want more risk, invest more of your funds in a diversified stock portfolio, don’t bet the farm on a… well a house, in Kiyosaki’s case.

So is everting he says nonsense?

I think there are two important takeaways.

- Save and invest – don’t live beyond your means. Try to save from your earnings, wherever they come from (boss or employee). Invest in your pension fund, or through your brokerage account, or have someone invest for you, who you trust.

- Sell – You cannot overstate the importance of selling yourself. Case in point: Robert Kiyosaki wrote a 300-page book. After each chapter, there is a summary of what he just wrote. And after the summary, there are quotes of what he just wrote. He literary repeats himself thrice. Of that actual “original” content of the book, half is an old man’s rant against taxes. Yet, he managed to sell 32 million copies! He then goes on to write: Rich Dad’s Cashflow Quadrant, Rich Dad’s Guide to Investing, Rich Dad Poor Dad for Teens, Retire Rich Retire Young. I mean the guy is a marketing genius! How many times can you write the exact same book and sell it! I am firmly convinced he earned way more selling himself to the readers than buying any bargain price property.

Hats off to you Robert K! That being said, I got my $5 for your book refunded from the Kindle store. I think you are rich enough, I will invest my money instead, my own way…

Detailed Example of How Leverage Works

Imagine you buy a house for $200,000 with $100,000 equity (own money) and $100,000 debt. Imagine you can rent out the house for 3% of its value a year ($6,000) and it also appreciates in value by 2% a year ($4,000) or a total of $10,000. That is a total return of the house is 5% a year ($10,000 / $200,000). That is pretty standard, even conservative by real estate standards. Imagine your debt costs 2%. You need to pay 2% interest on $100,000 or $2,000. The house generated $10,000 of return and you paid $2,000 to the bank in interest, so you have $8,000 left, which is an 8% return on your $100,000 of own capital. So the house returned 5%, but because it is partly funded with cheap debt, you realized 8% on your own investment. Note, what often confuses people is that they don’t only pay interest to the bank, they also pay down the principal, so they see more than $2,000 go out of their bank accounts. Imagine the principal repayment was an additional $1,000. What happens is that you pay $1,000 of cash to the bank, but now the bank owns $1,000 less of your house, (i.e. you increased the equity in your house). Therefore, while it stings you had to hand over your cash to the bank, your wealth did not change – you now just own “more house” and less cash. Your return on investment continues to be your earnings ($10,000) minus your cost of funding ($2,000), which is an 8% return, as we previously outlined.

One thought on “Rich Dad, Poor Advice”

Comments are closed.